The budget battle

The government’s finances get tangled up in a fight over who speaks for the Republican Party

Federal spending comes in two types: discretionary, which must be authorised every year; and mandatory, which is set in law. These labels are confusing because much discretionary spending is anything but: it includes funding for the justice system and defence. Since 1976 Congress has required itself to pass a dozen appropriations bills annually to cover this stuff. Unfortunately it has missed its deadline every year since 1994. To keep the lights on it has resorted to temporary resolutions to finance discretionary spending at existing levels until agreement can be reached, sometimes after a brief pause for effect.

Since 1981 government funding has expired without new money in place ten times, forcing a shutdown of operations, so in theory another is not too frightening a prospect. However nine of these shutdowns occurred over weekends, when much of what government does is closed anyway. The most recent was different: it lasted for 26 days between 1995 and 1996 and scarred everyone involved apart from the then Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, who has been advising Republicans to give it another go. The most senior Republicans in Congress now, John Boehner, the Speaker, and Eric Cantor, the House majority leader, demurred, suggesting separate bills to strangle the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), parts of which are due to come into force on October 1st, and to fund other spending.

Mr Gingrich’s political heirs, who hope that a general frustration with Washington will carry them to majorities in both chambers next year, rejected this. A group of Republican legislators led by Ted Cruz, a senator from Texas (pictured), their resolve stiffened by conservative institutions like the Heritage Foundation and the Club for Growth and with voluble support from grassroots activists, came up with a plan to tie the approval of funding the government to its denial for the health-care law. Thus the GOP could vote to keep the government going, forcing Democrats into voting against the bill and therefore for a shutdown in the name of their beloved Obamacare. This is a little like trying to plead not guilty to armed robbery on the ground that no shots were fired, but polls suggest the parties would shoulder roughly equal blame for a shutdown.

In the hope of making the plan stick, Republicans came up with a series of parliamentary manoeuvres baffling even by the standards of such things. First the Republican-controlled House passed a bill that contained the proviso to strip Obamacare of funding. Then a group of Republicans in the Senate postured at preventing Democrats from removing the key passage on health care by blocking a motion to bring the bill that Republicans supported to a vote. Mr Cruz, once described by a Republican presidential candidate as a “wacko bird”, spoke to the largely empty Senate for 21 hours as if he were addressing a crowd of thousands, breaking off for the occasional sip of water and to read his children a bedtime story.

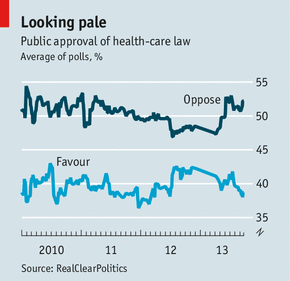

One more hostile vote is unlikely to change much at the federal level. Nor would Obamacare be delayed for long by a shutdown, as the main pieces of the Affordable Care Act do not depend on discretionary spending. But a fierce effort has begun in the states to ruin it by dissuading young people from signing up to insurance exchanges, in the hope that the system collapses under the cost of covering only those who will need plenty of expensive treatment. One advertisement features a young woman going for an appointment with a gynaecologist only to find herself inspected by a sinister cartoon Uncle Sam of the type usually found on banners at anti-American protests.

In their enthusiasm to make the most of what they think is a winning argument, the Republicans risk making two long-standing problems worse. The first is the split between those who look at Obamacare from Congress and those who see it from a state governor’s mansion. Several Republican governors are keen on bits of the law, including the extra money for Medicaid, which pays for health care for the poor. The second is a problem of perception. A report this year by the College Republican National Committee found that young voters see the GOP as “closed-minded” and “rigid”, whereas they give Mr Obama some credit for at least trying to fix things. It is hard to see how the current fight helps Republicans on either front.

If congressional Republicans fail to defund Obamacare this time, their resolve to fight hard over raising the debt ceiling will increase. The federal government takes in only 81 cents in revenue for every dollar it spends. The ceiling for borrowing was reached in May, since when the Treasury Department has shuffled money between government accounts to meet payments. It is likely to run out of room to continue doing so by mid-October. Because such a default would be the first in America’s history, it is probable that both sides will avoid triggering one. But it would be good to have more certainty from a borrower with debts of $16.7 trillion.

No comments:

Post a Comment