The Nicaragua-Costa Rica Border Dispute – A symptom of ‘Tico’ Decline?

By Victor Figueroa-Clark

Since the eruption of the border dispute between Costa Rica and Nicaragua in October 2010, the supposed causes of the conflict have been widely disseminated in the media. These analyses have often been lacking historical context, and have largely ascribed the dispute to nationalism. Meanwhile, in Central America, one is left to choose between allegations of Costa Rican imperialism on the one hand and Nicaraguan military ‘invasion’ on the other. It could appear that both sides have lost analytical perspective, and that we are witnessing another ‘typical’ bout of Latin American ‘hysteria’. However, ignoring the nationalistic tones of some outbursts and the way they are being portrayed in the English-language media, and instead concentrating on the origins of the recent dispute, we may find evidence of structural tensions in the region, and symptoms of worrying events in Costa Rica.

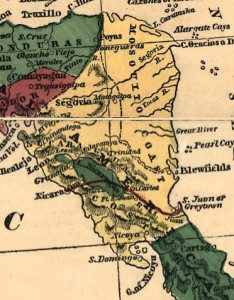

First though, a little history. Following independence from Spain, the countries of Central America were united in a Central American Federation. Nicaragua was at the time one of the largest Central American countries, with territory that extended northwards into what is today Honduras, and southwards to include the whole Nicoya peninsula and the province of Guanacaste, which is today the north of Costa Rica, from Pacific to Caribbean. The then-Tico (Costa Rican) border ran along the Matino river, several miles south of the San Juan river, which forms the current border. The loss of these regions (amounting to some 30 thousand square kilometres) in the 19th century is what stimulates Nicaraguan sensitivity to border issues. This sensitivity is exacerbated by what they perceive as the Colombian occupation of the San Andres islands, which severely limits the extent of Nicaragua’s claim to its maritime shelf in the Caribbean.

During the 1830s Costa Rican elites began to develop coffee farms, and their influence started to penetrate into the sparsely populated regions of Nicoya and Guanacaste. While Nicaraguan elites were engaged in a civil war, the Costa Ricans engineered the annexation of Guanacaste and Nicoya. The Nicaraguan government took the case before the Central American federation, but accepted the loss of the region. Then, in 1856, William Walker occupied Nicaragua with his Filibuster army, legalised slavery and cancelled existing contracts with American entrepreneur Cornelius Vanderbilt for a trans-isthsmian route that would link the Caribbean and the Pacific ocean, handing it over to a rival of his. Vanderbilt tried to engage the British and US governments in his efforts to overturn the cancellation, but they refused, and prompting Vanderbilt to pay the Costa Rican government to expel Walker’s army and reinstate his contracts.

Costa Rican forces duly helped the Nicaraguans defeat Walker, but their forces refused to return home at the end of the war. Tico troops occupied San Carlos and took over the San Juan river, arguing that it was their right by conquest. However, the Nicaraguan government refused to recognise this, despite the country’s parlous state in the wake of the war, and the Costa Ricans were forced to accept a new border which ran south of the San Juan river until it neared the Caribbean where it ran along the southern bank of the river itself, giving Tico coffee-growing elites access for their coffee exports. This is the origin of Costa Rica’s right to navigate the San Juan river.

This history of annexations and loss of territory is one part of the story of today’s conflict. There are other more modern elements to this dispute. First among these is the Costa Rican desire to profit from the development of any future route linking the Atlantic to the Pacific. The current Nicaraguan government has undertaken the dredging of the San Juan precisely to make the river navigable again, which will enable ships to enter Lake Nicaragua and will make the export of Nicaraguan agricultural products much cheaper. It may also then be completed via a rail link to a Pacific coast port, or perhaps a short canal across the Rivas isthmus to the sea. It must be noted that the access of Nicaragua’s interior to the sea is a crucial element within the FSLN government’s development strategy, which is to enable small-scale peasant producers to achieve a sustainable agricultural development to end the country’s dependency on food imports, and create a sustainable export industry initially based on agriculture. The money saved would be invested in infrastructure and other much-needed development projects to develop other sectors of the economy. If a cross-isthmian canal were completed, it too would bring in much needed revenue that would provide further funds for socio-economic development. Thus, the importance of the dispute for Nicaragua is not just historic and nationalist, it is also linked to its current socio-economic development project.

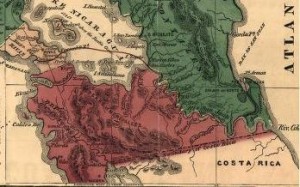

The second element of the conflict lies in Costa Rican motives. On the one hand, Costa Rica is seeking to defend its tourism industry, and its ability to export goods through to the Caribbean down the Colorado river. This river was historically a minor offshoot of the San Juan, but after the (unilateral) dredging of the Colorado river between 1948-1955, the major part of the water was diverted into Costa Rica, which has led directly to the silting up of the San Juan, cutting the Nicaraguan interior off from the Caribbean, and therefore from global markets for its produce. This dredging did, however, create a route for Costa Rican exports. The expanded river also created the location for part of the lucrative tourist industry that Costa Rica now enjoys.

Furthermore, Costa Rica’s agricultural border (the extent of its

cultivated lands) has extended ever further into the forests and

wetlands within the water basin of the San Juan. In recent years gold

mining along the border has also become a problem since it affects water

tables and leads to deforestation and pollution. This has caused

significant damage to wetlands on the Nicaraguan side of the border, but

more importantly has led to increased industrial pollution in the

protected wetlands around the mouth of the San Juan. Since Nicaragua

intends to use the San Juan river wetlands as a tourist destination to

rival those in north-eastern Costa Rica this pollution is an economic,

as well as environmental, concern.

Furthermore, Costa Rica’s agricultural border (the extent of its

cultivated lands) has extended ever further into the forests and

wetlands within the water basin of the San Juan. In recent years gold

mining along the border has also become a problem since it affects water

tables and leads to deforestation and pollution. This has caused

significant damage to wetlands on the Nicaraguan side of the border, but

more importantly has led to increased industrial pollution in the

protected wetlands around the mouth of the San Juan. Since Nicaragua

intends to use the San Juan river wetlands as a tourist destination to

rival those in north-eastern Costa Rica this pollution is an economic,

as well as environmental, concern.

There are other factors beyond mere economic competition and

nationalism that are influencing the situation. Since the election of

Daniel Ortega to the Nicaraguan presidency in 2006, Nicaragua has begun

transiting a development path that differs significantly from those of

its neighbours. Having learned from the mistakes of the 1980s

revolution, and lacking the backing of a superpower, the Sandinistas now

posit a gradual process of transformation that holds out rewards to

Nicaraguan business as well as the impoverished masses through a

strategic, integrated plan of national development. The development of

infrastructure alongside social development will enable growth for all

classes in Nicaraguan society. A crucial element of this policy is to

avoid direct conflict with the United States. Despite this, much of the

Nicaraguan middle class opposes the Sandinista government, because,

according to Eden Pastora (former Sandinista guerrilla and Contra

leader, who is currently in charge of the dredging operations of the San

Juan) “they no longer have control of the state or the governing party”

Instead, power now lies with the new generation of Sandinistas who

mostly come from among the low and mid-level ranks of the FSLN in the

1980s, and whose origins are among the poor. This opposition accounts

for the Nicaraguan government’s effective use of nationalism during the

dispute, since it helped to outmanoeuvre this domestic opposition.

There are other factors beyond mere economic competition and

nationalism that are influencing the situation. Since the election of

Daniel Ortega to the Nicaraguan presidency in 2006, Nicaragua has begun

transiting a development path that differs significantly from those of

its neighbours. Having learned from the mistakes of the 1980s

revolution, and lacking the backing of a superpower, the Sandinistas now

posit a gradual process of transformation that holds out rewards to

Nicaraguan business as well as the impoverished masses through a

strategic, integrated plan of national development. The development of

infrastructure alongside social development will enable growth for all

classes in Nicaraguan society. A crucial element of this policy is to

avoid direct conflict with the United States. Despite this, much of the

Nicaraguan middle class opposes the Sandinista government, because,

according to Eden Pastora (former Sandinista guerrilla and Contra

leader, who is currently in charge of the dredging operations of the San

Juan) “they no longer have control of the state or the governing party”

Instead, power now lies with the new generation of Sandinistas who

mostly come from among the low and mid-level ranks of the FSLN in the

1980s, and whose origins are among the poor. This opposition accounts

for the Nicaraguan government’s effective use of nationalism during the

dispute, since it helped to outmanoeuvre this domestic opposition.

The Nicaraguan development plan contrasts with the free-market policies of the current Costa Rican government. The Tico government is facing increasing domestic turmoil as a result due to rising unemployment and rising inequality. When Costa Rica approved joining CAFTA in 2007, it did so by the slimmest of margins (48-51%) despite months of heavy propaganda in favour and no disclosure of the conditions of signing. Since implementation in January 2009 (although it is early days) the economy has suffered. Unemployment has risen, and there has been a massive increase in the informal sector (street hawkers and so on) of the economy, which has also worsened working conditions for those in formal employment.

Frustration at growing inequality over the last 15 years has often been directed at Nicaraguan and other immigrants working in Costa Rican free trade zones, and agribusiness, but in this case this racism was not enough. As many governments have in the past, the current government is trying to distract attention from reasons for popular discontent with a nationalist cause. Although initially successful, the Tuesday 8th March International Court ruling on the border dispute appears to have alienated many ordinary Ticos, for whom the legal reverse is obvious.

To make the most of its nationalist cause, Costa Rica portrayed itself, both at home and abroad, as the victim of Nicaraguan aggression, an interesting allegation that made much of the absence of a Costa Rican army. However, the Nicaraguans point out that despite not having an army in name, Costa Rica does possess a well-trained and heavily armed police force, paid for by a defence budget much higher than Nicaragua’s own. The size of the two countries’ armed forces is roughly the same. According to globalsecurity.org Costa Rica’s military spending in 2007 stood at just under $293 million, and Nicaragua’s at just under $100 million. This helps put Costa Rica’s deployment of 2000 Fuerza Publica ‘police’ to the border area in October 2010 in perspective and demonstrates a rather aggressive posture towards problem solving.

The spark for Costa Rica to launch the dispute was provided by the alleged occupation of Costa Rican territory by Nicaraguan troops. These troops were operating in the San Juan region with the knowledge of Costa Rican authorities, who had been informed of an anti-drugs operation during which six Honduran drugs traffickers were arrested and two Nicaraguan traffickers fled to Costa Rica. It was only when dredging operations began on the 18th of October that the Costa Ricans accused Nicaragua of invasion, and subsequently mobilised armed forces to the border, setting off the international scandal which has ultimately backfired. It appears that the strategy of the Costa Rican government was to declare invasion, and have the OAS rally behind it. In the end the Costa Rican government was forced to accept the Nicaraguan position on the dispute, which was to take it to the International Court at The Hague. Not only did this show that the conflict was not about an ‘invasion’, but rather a border dispute, it also showed that Nicaragua is still willing to resolve problems through dialogue, much as the Sandinista government did in the 1980s.

It is interesting to ponder what has led the Costa Rican government to make such a rash move against its northern neighbour. There are several likely causes. Since the 1980s Costa Rica has suffered increasing inequality and parallel social discontent. There was significant polarisation over the signing of CAFTA, which has continued since. Interestingly, according to a Wikileaks cable, the repression of labour mobilisations in 2007 counted on help from the US embassy, which participated in planning for the protests, and used anti-drugs funds to pay for the transportation of Tico police to protest sites. The crackdown on these mobilisations has led the Tico government being condemned by the ILO during the summer of 2010. The ITUC also reported that “The fundamental right to negotiate collective bargaining agreements is under serious threat.”

As has occurred in Mexico since joining NAFTA and in Colombia, the pursuit of free trade policies has dire consequences for the bulk of the population, and this has lead to a search for alternative sources of income. In Central America, a key transit point for the drugs trade between Colombia and the US, one of these alternative sources of income is the drugs trade. It is no coincidence that cocaine became an even more serious problem in Colombia after the deregulation of coffee prices, and no coincidence that Mexican cartels have found a large pool of labour in the now-unemployed peasants driven off the land by cheap imports of government-subsidised maize from the US. In Costa Rica, opening the market to subsidised exports will destroy domestic agriculture, exacerbating the growing inequality that is leading many to supplement their incomes with income from the drugs trade.

Drugs trafficking has a relatively long history in Costa Rica (although it did not penetrate Costa Rican institutions until more recently). The presence in Costa Rica of drugs traffickers began during the 1980s, when the CIA was setting up cocaine supply routes from Colombia, via Panama, Costa Rica and Honduras in order to finance the Contras. With so much time to make themselves at home, Colombian paramilitary drugs gangs have been able to penetrate Costa Rican anti-drugs units, and establish secure storage sites across the country. The absence of Tico authorities from the more remote areas of the country gives the traffickers a free hand. This is actually the case in the San Juan river area, where locals report that prior to the dispute the nearest police unit was 25km away and the area did not have a permanent police presence.

The worry for Costa Ricans witnessing the collapse of their welfare state, growing inequality and the penetration of institutions by the drugs trade, must be that past experiences in Latin America indicate a correlation between the application of neoliberal economic policies and deteriorating social indicators and increased violent social conflict. When combined with the drugs trade, this leads to a toxic situation. Faced with internal unrest, but unwilling or unable to apply policies to alleviate the problems which cause it, neoliberal governments crack down on social organisations opposing their policies, and militarise their response to crime. Despite their differences, the current situations in Mexico, Colombia, Jamaica, Honduras and Guatemala, indicate a likely future for Costa Rica if governments continue to apply harsh economic and security policies without attempting to deal with the socio-economic causes of instability.

Thus the border dispute is not just about nationalism or economics, it is also about the confrontation of two development models, one which follows the neoliberal mantra of ever-more open markets, where the state exists to dampen resulting popular protest, and another which is trying out a development strategy tailored to the context and requirements of the hemisphere’s second poorest country, where development requires a controlled market and state investment. In this sense the conflict is a manifestation of the conflict that has beset Latin America since independence.

Since the eruption of the border dispute between Costa Rica and Nicaragua in October 2010, the supposed causes of the conflict have been widely disseminated in the media. These analyses have often been lacking historical context, and have largely ascribed the dispute to nationalism. Meanwhile, in Central America, one is left to choose between allegations of Costa Rican imperialism on the one hand and Nicaraguan military ‘invasion’ on the other. It could appear that both sides have lost analytical perspective, and that we are witnessing another ‘typical’ bout of Latin American ‘hysteria’. However, ignoring the nationalistic tones of some outbursts and the way they are being portrayed in the English-language media, and instead concentrating on the origins of the recent dispute, we may find evidence of structural tensions in the region, and symptoms of worrying events in Costa Rica.

First though, a little history. Following independence from Spain, the countries of Central America were united in a Central American Federation. Nicaragua was at the time one of the largest Central American countries, with territory that extended northwards into what is today Honduras, and southwards to include the whole Nicoya peninsula and the province of Guanacaste, which is today the north of Costa Rica, from Pacific to Caribbean. The then-Tico (Costa Rican) border ran along the Matino river, several miles south of the San Juan river, which forms the current border. The loss of these regions (amounting to some 30 thousand square kilometres) in the 19th century is what stimulates Nicaraguan sensitivity to border issues. This sensitivity is exacerbated by what they perceive as the Colombian occupation of the San Andres islands, which severely limits the extent of Nicaragua’s claim to its maritime shelf in the Caribbean.

During the 1830s Costa Rican elites began to develop coffee farms, and their influence started to penetrate into the sparsely populated regions of Nicoya and Guanacaste. While Nicaraguan elites were engaged in a civil war, the Costa Ricans engineered the annexation of Guanacaste and Nicoya. The Nicaraguan government took the case before the Central American federation, but accepted the loss of the region. Then, in 1856, William Walker occupied Nicaragua with his Filibuster army, legalised slavery and cancelled existing contracts with American entrepreneur Cornelius Vanderbilt for a trans-isthsmian route that would link the Caribbean and the Pacific ocean, handing it over to a rival of his. Vanderbilt tried to engage the British and US governments in his efforts to overturn the cancellation, but they refused, and prompting Vanderbilt to pay the Costa Rican government to expel Walker’s army and reinstate his contracts.

Costa Rican forces duly helped the Nicaraguans defeat Walker, but their forces refused to return home at the end of the war. Tico troops occupied San Carlos and took over the San Juan river, arguing that it was their right by conquest. However, the Nicaraguan government refused to recognise this, despite the country’s parlous state in the wake of the war, and the Costa Ricans were forced to accept a new border which ran south of the San Juan river until it neared the Caribbean where it ran along the southern bank of the river itself, giving Tico coffee-growing elites access for their coffee exports. This is the origin of Costa Rica’s right to navigate the San Juan river.

This history of annexations and loss of territory is one part of the story of today’s conflict. There are other more modern elements to this dispute. First among these is the Costa Rican desire to profit from the development of any future route linking the Atlantic to the Pacific. The current Nicaraguan government has undertaken the dredging of the San Juan precisely to make the river navigable again, which will enable ships to enter Lake Nicaragua and will make the export of Nicaraguan agricultural products much cheaper. It may also then be completed via a rail link to a Pacific coast port, or perhaps a short canal across the Rivas isthmus to the sea. It must be noted that the access of Nicaragua’s interior to the sea is a crucial element within the FSLN government’s development strategy, which is to enable small-scale peasant producers to achieve a sustainable agricultural development to end the country’s dependency on food imports, and create a sustainable export industry initially based on agriculture. The money saved would be invested in infrastructure and other much-needed development projects to develop other sectors of the economy. If a cross-isthmian canal were completed, it too would bring in much needed revenue that would provide further funds for socio-economic development. Thus, the importance of the dispute for Nicaragua is not just historic and nationalist, it is also linked to its current socio-economic development project.

The second element of the conflict lies in Costa Rican motives. On the one hand, Costa Rica is seeking to defend its tourism industry, and its ability to export goods through to the Caribbean down the Colorado river. This river was historically a minor offshoot of the San Juan, but after the (unilateral) dredging of the Colorado river between 1948-1955, the major part of the water was diverted into Costa Rica, which has led directly to the silting up of the San Juan, cutting the Nicaraguan interior off from the Caribbean, and therefore from global markets for its produce. This dredging did, however, create a route for Costa Rican exports. The expanded river also created the location for part of the lucrative tourist industry that Costa Rica now enjoys.

San

Juan river relative to the Colorado in the 19th century (thinner line

at the bottom left). Source: Center for Military History, Managua

The

map shows the change in flow of the San Juan following Tico dredging.

The San Juan is at top right. Source: Center for Military History,

Managua

The Nicaraguan development plan contrasts with the free-market policies of the current Costa Rican government. The Tico government is facing increasing domestic turmoil as a result due to rising unemployment and rising inequality. When Costa Rica approved joining CAFTA in 2007, it did so by the slimmest of margins (48-51%) despite months of heavy propaganda in favour and no disclosure of the conditions of signing. Since implementation in January 2009 (although it is early days) the economy has suffered. Unemployment has risen, and there has been a massive increase in the informal sector (street hawkers and so on) of the economy, which has also worsened working conditions for those in formal employment.

Frustration at growing inequality over the last 15 years has often been directed at Nicaraguan and other immigrants working in Costa Rican free trade zones, and agribusiness, but in this case this racism was not enough. As many governments have in the past, the current government is trying to distract attention from reasons for popular discontent with a nationalist cause. Although initially successful, the Tuesday 8th March International Court ruling on the border dispute appears to have alienated many ordinary Ticos, for whom the legal reverse is obvious.

To make the most of its nationalist cause, Costa Rica portrayed itself, both at home and abroad, as the victim of Nicaraguan aggression, an interesting allegation that made much of the absence of a Costa Rican army. However, the Nicaraguans point out that despite not having an army in name, Costa Rica does possess a well-trained and heavily armed police force, paid for by a defence budget much higher than Nicaragua’s own. The size of the two countries’ armed forces is roughly the same. According to globalsecurity.org Costa Rica’s military spending in 2007 stood at just under $293 million, and Nicaragua’s at just under $100 million. This helps put Costa Rica’s deployment of 2000 Fuerza Publica ‘police’ to the border area in October 2010 in perspective and demonstrates a rather aggressive posture towards problem solving.

The spark for Costa Rica to launch the dispute was provided by the alleged occupation of Costa Rican territory by Nicaraguan troops. These troops were operating in the San Juan region with the knowledge of Costa Rican authorities, who had been informed of an anti-drugs operation during which six Honduran drugs traffickers were arrested and two Nicaraguan traffickers fled to Costa Rica. It was only when dredging operations began on the 18th of October that the Costa Ricans accused Nicaragua of invasion, and subsequently mobilised armed forces to the border, setting off the international scandal which has ultimately backfired. It appears that the strategy of the Costa Rican government was to declare invasion, and have the OAS rally behind it. In the end the Costa Rican government was forced to accept the Nicaraguan position on the dispute, which was to take it to the International Court at The Hague. Not only did this show that the conflict was not about an ‘invasion’, but rather a border dispute, it also showed that Nicaragua is still willing to resolve problems through dialogue, much as the Sandinista government did in the 1980s.

It is interesting to ponder what has led the Costa Rican government to make such a rash move against its northern neighbour. There are several likely causes. Since the 1980s Costa Rica has suffered increasing inequality and parallel social discontent. There was significant polarisation over the signing of CAFTA, which has continued since. Interestingly, according to a Wikileaks cable, the repression of labour mobilisations in 2007 counted on help from the US embassy, which participated in planning for the protests, and used anti-drugs funds to pay for the transportation of Tico police to protest sites. The crackdown on these mobilisations has led the Tico government being condemned by the ILO during the summer of 2010. The ITUC also reported that “The fundamental right to negotiate collective bargaining agreements is under serious threat.”

As has occurred in Mexico since joining NAFTA and in Colombia, the pursuit of free trade policies has dire consequences for the bulk of the population, and this has lead to a search for alternative sources of income. In Central America, a key transit point for the drugs trade between Colombia and the US, one of these alternative sources of income is the drugs trade. It is no coincidence that cocaine became an even more serious problem in Colombia after the deregulation of coffee prices, and no coincidence that Mexican cartels have found a large pool of labour in the now-unemployed peasants driven off the land by cheap imports of government-subsidised maize from the US. In Costa Rica, opening the market to subsidised exports will destroy domestic agriculture, exacerbating the growing inequality that is leading many to supplement their incomes with income from the drugs trade.

Drugs trafficking has a relatively long history in Costa Rica (although it did not penetrate Costa Rican institutions until more recently). The presence in Costa Rica of drugs traffickers began during the 1980s, when the CIA was setting up cocaine supply routes from Colombia, via Panama, Costa Rica and Honduras in order to finance the Contras. With so much time to make themselves at home, Colombian paramilitary drugs gangs have been able to penetrate Costa Rican anti-drugs units, and establish secure storage sites across the country. The absence of Tico authorities from the more remote areas of the country gives the traffickers a free hand. This is actually the case in the San Juan river area, where locals report that prior to the dispute the nearest police unit was 25km away and the area did not have a permanent police presence.

The worry for Costa Ricans witnessing the collapse of their welfare state, growing inequality and the penetration of institutions by the drugs trade, must be that past experiences in Latin America indicate a correlation between the application of neoliberal economic policies and deteriorating social indicators and increased violent social conflict. When combined with the drugs trade, this leads to a toxic situation. Faced with internal unrest, but unwilling or unable to apply policies to alleviate the problems which cause it, neoliberal governments crack down on social organisations opposing their policies, and militarise their response to crime. Despite their differences, the current situations in Mexico, Colombia, Jamaica, Honduras and Guatemala, indicate a likely future for Costa Rica if governments continue to apply harsh economic and security policies without attempting to deal with the socio-economic causes of instability.

Thus the border dispute is not just about nationalism or economics, it is also about the confrontation of two development models, one which follows the neoliberal mantra of ever-more open markets, where the state exists to dampen resulting popular protest, and another which is trying out a development strategy tailored to the context and requirements of the hemisphere’s second poorest country, where development requires a controlled market and state investment. In this sense the conflict is a manifestation of the conflict that has beset Latin America since independence.

Victor Figueroa Clark is a PhD candidate in the International History

department at the LSE. His research looks at the role of Chilean

internationalists in Central America in the 1980s. He is a programme

assistant on the Latin America International Affairs Programme.

No comments:

Post a Comment