The incarceration of black men has had far-reaching effects on their children. Maybe that’s why my family kept it a secret

VICTORIA BOND

My mother dated a limousine driver when I was kid. And when he visited, cruising down my narrow, working-class block in his shiny black limo, not only did all of the neighborhood kids assume that he was my father; they also assumed, awe-struck, that he was rich. I knew it wasn’t true, but I could never bring myself to dispel the story. It set me apart, made me look good – and back then, I wasn’t sure what the truth about my real father was.

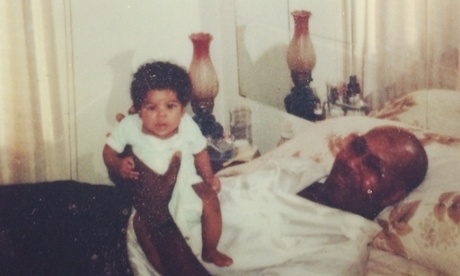

My family doled out information about him in tantalizing morsels. My mother told me that, when I was a baby, she rocked me to sleep while singing “Your daddy’s rich and your mama’s good lookin...”. My aunt laughed about how, on visits to California when she was 13, my grandfather took her out for driving lessons in my father’s Rolls as well as his Mercedes, without my parents’ knowledge. My grandpa’s eyes widened when he recalled visiting my father’s gas station, car wash and contract cleaning businesses in the late 70s, marvelling at their prosperity.

As a little girl living in an African American working class neighborhood in northern New Jersey – where certain blocks were off limits because they hosted crack houses – those tales of West Coast wealth and glamour made me realize how easily riches can turn into rags.

When I was nine, I got my first-ever letter from my father, and, with it, a glimpse of understanding about where some of the other absent dads in my community were (and where others, unfortunately, would soon be). In tall, loopy letters on yellow legal paper, my father explained that he was in prison, that he had been for most of my life and that he loved me very much. I wasn’t sure how to feel – and, frankly, I still don’t.

What I couldn’t know then was that my father had traded his actual life for the illusion of “the good life”.

My father spent more than two decades, cumulatively, behind bars. Along with the loss of his freedom, his repeated offenses stripped him of the opportunity to be present for long periods of most of his eight children’s young lives – not to mention the means to live lawfully and the right to vote. My father, born in the 1930s, was a kind of pioneer subject of the prison pipeline system that continues to carry black men down the road of less-than-full citizenship and structural unemployment, robbing many African American families of financial and emotional stability.

He was, it seems, emblematic of the kingpin drug dealer stereotype that would eventually be used by the political right to bait a public hungry for the drug war (along with the crack mother and other figures).

Works such as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness demonstrate the inequality built into the 30-year war on drugs. African Americans represent just 12% of the total population of drug users, but they are 38% of those arrested for drug offenses and 59% of those in state prison for a drug offense. A special report released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in 2010 found that, like my father, drug offenders in state and federal prisons were more likely to have children than violent offenders – and another Bureau of Justice Statistics report on incarcerated parents found that nearly half of all imprisoned parents were black.

As imprisonment has become increasingly common for black men, parental incarceration has become the norm for black children – with far-reaching, negative results. Sociologist Anna R Haskins found that the children of incarcerated fathers are less cognitively prepared to enter school than their counterparts whose parents are not in the criminal justice system. Similarly, recent data analysis suggests that having a parent in prison is associated with an increase in antisocial behavior and unemployment. Shockingly, in 2000, over one in 10 black children under age 10 had a father in prison or jail. It then comes as little surprise that 26% children in foster care in American are black (though only 13.6% of the overall population of the US is), and many of them there due to the incarceration of a custodial parent.

The upshot of the devastating trend of mass incarceration is that the resources – economic, civic, and familial – of African Americans have been dramatically eroded. Ironically, the prejudicial application of the American justice system has destabilized the African American family, mirroring the societal ravages of drug addiction the so-called war on drugs sought to end.

Children are deprived of their parents through addiction and incarceration, which have a vicious compounding effect; as these children enter, exit and often age out of foster care, they are disproportionately likely to end up homeless or incarcerated. Disenfranchisement becomes a congenital disease passed from one generation to the next.

I was lucky. I was spared what can be the humiliating visits to correctional facilities by my family’s secret-keeping, and my mother’s close family meant that my life was a lot more stable than those of many of the other kids in my neighborhood. But, because my father’s absence was a mystery for a large chunk of my childhood, from the time I met him at 12 (upon his release) until he died of a stroke in 1999 (still on parole), I never trusted him. Neither did the system.

My mother dated a limousine driver when I was kid. And when he visited, cruising down my narrow, working-class block in his shiny black limo, not only did all of the neighborhood kids assume that he was my father; they also assumed, awe-struck, that he was rich. I knew it wasn’t true, but I could never bring myself to dispel the story. It set me apart, made me look good – and back then, I wasn’t sure what the truth about my real father was.

My family doled out information about him in tantalizing morsels. My mother told me that, when I was a baby, she rocked me to sleep while singing “Your daddy’s rich and your mama’s good lookin...”. My aunt laughed about how, on visits to California when she was 13, my grandfather took her out for driving lessons in my father’s Rolls as well as his Mercedes, without my parents’ knowledge. My grandpa’s eyes widened when he recalled visiting my father’s gas station, car wash and contract cleaning businesses in the late 70s, marvelling at their prosperity.

As a little girl living in an African American working class neighborhood in northern New Jersey – where certain blocks were off limits because they hosted crack houses – those tales of West Coast wealth and glamour made me realize how easily riches can turn into rags.

When I was nine, I got my first-ever letter from my father, and, with it, a glimpse of understanding about where some of the other absent dads in my community were (and where others, unfortunately, would soon be). In tall, loopy letters on yellow legal paper, my father explained that he was in prison, that he had been for most of my life and that he loved me very much. I wasn’t sure how to feel – and, frankly, I still don’t.

What I couldn’t know then was that my father had traded his actual life for the illusion of “the good life”.

My father spent more than two decades, cumulatively, behind bars. Along with the loss of his freedom, his repeated offenses stripped him of the opportunity to be present for long periods of most of his eight children’s young lives – not to mention the means to live lawfully and the right to vote. My father, born in the 1930s, was a kind of pioneer subject of the prison pipeline system that continues to carry black men down the road of less-than-full citizenship and structural unemployment, robbing many African American families of financial and emotional stability.

He was, it seems, emblematic of the kingpin drug dealer stereotype that would eventually be used by the political right to bait a public hungry for the drug war (along with the crack mother and other figures).

Works such as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness demonstrate the inequality built into the 30-year war on drugs. African Americans represent just 12% of the total population of drug users, but they are 38% of those arrested for drug offenses and 59% of those in state prison for a drug offense. A special report released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in 2010 found that, like my father, drug offenders in state and federal prisons were more likely to have children than violent offenders – and another Bureau of Justice Statistics report on incarcerated parents found that nearly half of all imprisoned parents were black.

As imprisonment has become increasingly common for black men, parental incarceration has become the norm for black children – with far-reaching, negative results. Sociologist Anna R Haskins found that the children of incarcerated fathers are less cognitively prepared to enter school than their counterparts whose parents are not in the criminal justice system. Similarly, recent data analysis suggests that having a parent in prison is associated with an increase in antisocial behavior and unemployment. Shockingly, in 2000, over one in 10 black children under age 10 had a father in prison or jail. It then comes as little surprise that 26% children in foster care in American are black (though only 13.6% of the overall population of the US is), and many of them there due to the incarceration of a custodial parent.

The upshot of the devastating trend of mass incarceration is that the resources – economic, civic, and familial – of African Americans have been dramatically eroded. Ironically, the prejudicial application of the American justice system has destabilized the African American family, mirroring the societal ravages of drug addiction the so-called war on drugs sought to end.

Children are deprived of their parents through addiction and incarceration, which have a vicious compounding effect; as these children enter, exit and often age out of foster care, they are disproportionately likely to end up homeless or incarcerated. Disenfranchisement becomes a congenital disease passed from one generation to the next.

I was lucky. I was spared what can be the humiliating visits to correctional facilities by my family’s secret-keeping, and my mother’s close family meant that my life was a lot more stable than those of many of the other kids in my neighborhood. But, because my father’s absence was a mystery for a large chunk of my childhood, from the time I met him at 12 (upon his release) until he died of a stroke in 1999 (still on parole), I never trusted him. Neither did the system.

No comments:

Post a Comment