\ By Charlotte Alfred

One month later, 43 students from the Ayotzinapa rural teachers college are still missing and presumed dead. Instead of finding the students, authorities investigating the events of Sept. 26 have instead found other horrors: a string of mass graves, police working for drug cartels and government officials at the helm of a dark underworld.

The hunt for the students has laid bare the brutality and lawlessness in parts of Mexico still under the grip of the cartels, despite years of Mexico’s war on drugs.

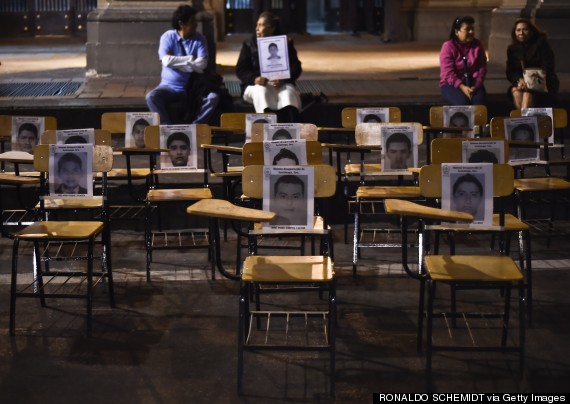

Chairs with portraits of missing students are seen during a march for the 43 missing students in Mexico City, Oct. 22, 2014. (RONALDO SCHEMIDT/AFP/Getty Images)

Here are some of the disturbing findings of the Mexican government's investigation:

Last Sighting Of The Students

The students -- men in their late teens and early 20s -- were studying to become teachers in rural Mexico at a college with a history of radical leftist activism, the BBC reported. That Friday, they went out to demonstrate against hiring discrimination and solicit funds for an upcoming protest march.

Witnesses have said that the students were in Iguala, a city in southern Mexico, when they came under fire from police.

By the end of the night, six people were left dead. The body of one student was later found with his face skinned and eyes gouged out, the New Yorker reported, "the signature of a Mexican organized-crime assassination."

Some of the students escaped Iguala, but 43 of them have not been seen since that night. Survivors described their classmates being taken away by police, but authorities denied they were in state custody.

When the students didn't return and relatives and sympathizers took to the streets in protest, Mexico's federal government launched an investigation.

The City's Former Mayor And His Wife Allegedly Control The Local Drug Cartel

According to the investigation, former Iguala Mayor José Luis Abarca Velázquez instructed municipal police to stop the student protests at all costs.

Abarca and his wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda Villa, are the “probable masterminds” behind the crime and are on the run from arrest, according to Mexico’s attorney general.

The investigation has led to allegations that Abarca and Pineda were the heads of a murderous personal fiefdom in collaboration with the local drug cartel -- the Guerreros Unidos.

Former Iguala Mayor Jose Luis Abarca and his wife, Maria de los Angeles Pineda Villa, at a meeting in Chilpancingo, Mexico, May 8, 2014. (AP Photo/Alejandrino Gonzalez, File)

After his arrest, the head of the cartel told investigators that Pineda -- the daughter and sister of cartel members -- is the “key operator” of the criminal network in Iguala. When the students' protest risked disrupting an event launching her own bid for the mayor’s office, Pineda gave the order to “teach them a lesson,” the cartel chief told authorities, according to the Daily Beast.

Despite expressions of shock by the Mexican government, local residents say officials turned a blind eye to the couple’s gang connections. "Everyone knew about their presumed connections to organized crime," Alejandro Encinas, a senator from the mayor's Democratic Revolution Party, told the Associated Press. "Nobody did anything, not the federal government, not the state government, not the party leadership."

Investigators Say Police Worked As The Cartel’s Hit Men

Investigators said that police delivered the 43 missing students to members of the Guerreros Unidos cartel, telling them that the students were members of a rival drug gang.

Guerreros Unidos hit men admitted to killing some of the students and dumping them in a pit -- although their bodies have not yet been identified.

In custody, Guerreros Unidos members named at least 30 local police officers they said were working directly for the cartel. “I wouldn't call these police, 'police.' I would call them hit men,” Mexican federal Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam told reporters.

Dozens of police have since been arrested, and authorities said some have confessed to being involved. Iguala’s police chief is also on the run. Federal police officers have taken over law enforcement in Iguala, disarming the entire force.

Municipal police officers suspected of involvement in the students' disappearance are taken to waiting transport at the attorney general's organized crime unit in Mexico City, Oct. 17, 2014. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, File)

Meanwhile, a banner demanding the policemen’s release appeared in Iguala, signed by the Guerreros Unidos cartel. "Or else we will reveal the names of all the politicians who work for us. The war is just beginning," the sign threatened.

The Cartel’s Control Likely Goes Far Beyond One City

The Guerreros Unidos cartel is thought to control drug routes in Guerrero state -- where Iguala is located -- and neighboring Morelos. And the collusion of local authorities in their operation likely runs far wider than Iguala.

Federal police have taken control of more than 12 municipalities in southern Mexico after finding “presumed links to organized crime” in their police forces, Mexico National Security Commissioner Monte Alejandro Rubido said.

The cartel is one of several regional splinter groups from the notorious Sinaloa Cartel to emerge around 2011, according to investigative journalism group InSight Crime. Violence has exploded as the gangs battle for territory, and Guerrero had the highest murder rate in Mexico in 2013, the group said.

Many, Many More Are Missing And Dead

In their search for any trace of the students, investigators have found at least 12 mass graves with dozens of unidentified bodies near Iguala. So far, authorities say none of the remains match the missing students.

The gruesome discoveries confirmed some of the residents’ worst fears -- that the hills above the city were being used as a cemetery for the disappeared.

View of a grave discovered in Pueblo Viejo, in the outskirts of Iguala, Guerrero state, Mexico, on Oct. 6, 2014. (Pedro PARDO/AFP/Getty Images)

Already this year, 150 bodies have been found in secret graves throughout Guerrero state, InSight Crime reports, citing the state’s forensic office.

Across Mexico, more than 20,000 people have disappeared in the last eight years, according to government figures. Human Rights Watch’s Nik Steinberg, who has extensively investigated the disappearances, wrote in Foreign Policy earlier this year that if even half of the cases are verified, this represents “one of the worst waves of disappearances in the Americas in decades.”

“The evidence suggests not only that authorities have failed to investigate disappearances, but also, in many cases, that soldiers and police have helped to carry them out,” he wrote in a story published before the Iguala students vanished.

People protest the students' disappearance in Guadalajara, Mexico, on Oct. 8, 2014. (Servando Gomez Camarillo/LatinContent/Getty Images)

In the meantime, the students' families and supporters are holding out hope that they will be found.

“Today all Mexico resounds with the cry 'They took them alive, we want them back alive,'" Mexican poet and former diplomat Homero Aridjis wrote in a recent blog post for The WorldPost. “Mexicans are fed up with living in a pervasive state of corruption and impunity,” he said.

The students’ disappearance and the allegations of official complicity have brought thousands of outraged protesters onto the streets of Mexico to demand their return -- and justice.

Demonstrators protest the disappearance of the students on Oct. 17, 2014 in Acapulco, Mexico. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

A student paints 'Repressive State' on the windows of the attorney general's office in Mexico City during a protest for the missing students, Oct. 15, 2014. (OMAR TORRES/AFP/Getty Images)

No comments:

Post a Comment