Protests in Mexico

The president proposes laws to fight crime. Mexicans want more than that

More enlightened than her government

AN UNUSUAL cry has rung out in recent weeks at football matches, rock

concerts and protest marches in Mexico. Crowds of people chant in

unison the numbers from one to 43, representing each of the students who

disappeared in September in the south-western state of Guerrero. They

end with a shout: “¡Justicia!”They are not merely demanding justice for the missing 43, who the government claims were massacred by municipal authorities and drug-traffickers. The cry also appears to reflect an exhaustion of patience with a system—political, economic and legal—that exempts from the rule of law those who can buy or bargain their way around it, such as corrupt politicians, privileged businessmen and narcos.

The call unites left and right, though no political party has seized upon it. “We haven’t had this sort of demand since the [1910-17] revolution,” says Sabino Bastidas, a political analyst. “It’s no longer for democracy or security. The biggest inequality in Mexico is in the justice system.”

President Enrique Peña Nieto responded to the clamour on December 1st, his second anniversary in office, by sending seven proposed constitutional amendments to Congress. Borrowing from the example of West Germany in the 1970s, they aim to replace Mexico’s 1,800 municipal police forces with 32 state forces and to make towns pay state governments for security. The federal government would gain the power to take over a local one if it had been infiltrated by organised crime. German unification in the 1990s inspired another reform: a diversion of resources from rich regions to the impoverished south, where criminality has taken root.

Many of the proposals are contentious and not all are well conceived. Some municipal police forces—such as those of Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez—have been transformed for the better in recent years, and now outperform their state equivalents. In some states, governors and their police forces are just as corrupt as the municipal authorities.

In handing the bills to Congress rather than taking executive action, Mr Peña has given the opposition a chance to block the package. He can no longer rely on the so-called Pact for Mexico, which he struck with the opposition two years ago to enact economic reforms. It is dead.

Mexicans will have to wait until next year for measures to address directly the inequities in the justice system. In presenting his police reforms, Mr Peña acknowledged the need for them. He spoke of “day-to-day” injustices—a woman unable to obtain a divorce judgment, a worker whose employer refuses to pay him. Resolving such complaints through the legal system is so costly and time-consuming that most people do not bother. Mr Peña has asked a university in Mexico City to come up with proposals within 90 days.

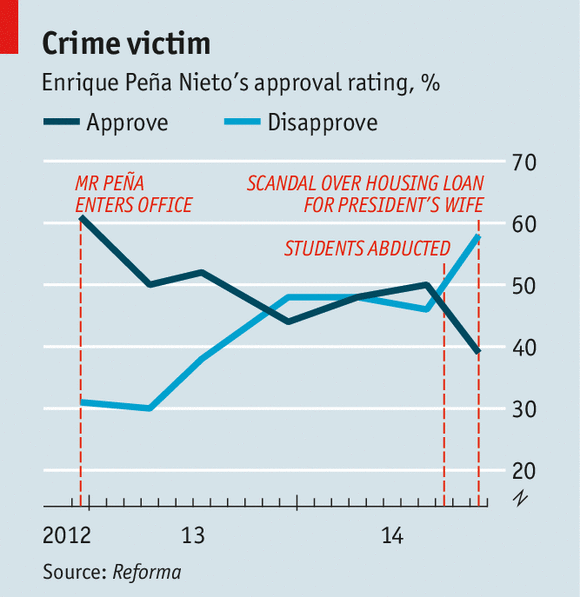

He only vaguely addressed the other subject that has darkened the mood since the disappearance of the students: the ethics of politicians. Mexicans have been scandalised that the mayor who allegedly ordered the killings went uninvestigated by federal authorities. Then they learned that the president’s wife had taken a multi-million-dollar housing loan from a company connected to a construction magnate who has won recent government contracts. Although Mr Peña has denied any conflict of interest and published a list of his assets, the revelations have hurt his credibility. Politicians from all parties are often exposed for using public money as electoral slush funds.

Luis de la Calle, an economist, says that Mr Peña’s judicial reforms should target politicians’ vested interests, just as the economic reforms targeted those of big business. This can partly be done by strengthening institutions of transparency and accountability. Mr de la Calle suggests limiting the time allowed for electoral campaigning, so that politicians see less need to finance themselves illicitly. Eventually, he believes, a new focus on law and order will make Mexico a more modern country.

No comments:

Post a Comment