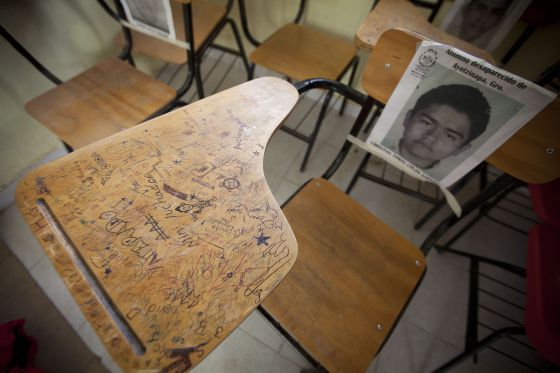

Reconstructing the events surrounding the capture and death of 43 Mexican students

The night of September 26, 23-year-old Ernesto Guerrero saw the mouth of a Colt AR-15 pointing at him.

– Go or I kill you.

He didn’t know it at the time, but the officer was saving

him from certain death. It was nothing to do with chance or pity, but

plain logistics. As Ernesto would remember weeks later, municipal police

officers had dozens of student teachers from the Escuela Rural Normal

de Ayotzinapa lying face down on the asphalt and were taking them away

in trucks. The vehicles were so full that Iguala police asked officers

from the nearby town of Cocula for help and when Ernesto, armed with

courage, approached to ask about the fate of his friends, they no longer

had time or space for one more. They pointed the rifle at him and

warned him to go away. “I saw my schoolmates disappear down the avenue,”

he remembers. That was the last time he knew anything about them.

That day, Ernesto and two busloads of almost 100 student

teachers had arrived in Iguala from Ayotzinapa. The radical and

rebellious students were going to collect funds for their activities, as

they had on other occasions. This meant panhandling on the city’s main

roads, entering a few business establishments and even cutting off a

street.

Their arrival did not go unnoticed. According to the

timeline of events put together by Mexico’s Prosecutor General’s Office,

the drug cartels’ hawks followed the students and alerted municipal

police of their presence. The normalistas, as they are known,

were not welcome. After the torture and murder of peasant leader Arturo

Hernández Cardona in June 2013, students had blamed Iguala’s mayor, José Luis Abarca Velázquez, and attacked his office.

The hitmen and police, who cooperated perfectly in Iguala,

thought the students were going to repeat the raid not against the mayor

but against someone even more powerful: his wife, María de los Ángeles

Pineda Villa.

Police investigations say she was in charge of the finances

of the local Guerreros Unidos cartel. Her ties to the drug trade ran

deep. She is the daughter of an old operative of Arturo “the Boss of

Bosses” Beltrán Leyva, and her own brothers had created Guerreros Unidos

to fight off the Zetas and La Familia Michoacana cartels at Beltrán

Leyva’s request. When both were executed and thrown into a gutter on the

side of Cuernavaca highway, she took the reigns in Iguala, where she

and her husband began a stunning social climb, which she was about to

complete with her latest ambition: to be elected mayor in 2015. She had

organized a huge event to be held in the town’s main square on September

26. It was to be the beginning of her electoral race.

The arrival of the normalistas, hooded, rebellious, eager

to protest, made them fear the event would be disrupted. The mayor

ordered his henchmen to stop the students at all costs and, according to

various versions of events, to hand them over to Guerreros Unidos. The

order was followed blindly.

It may never be known exactly how the barbaric events

reached the extremes they did, but police investigations say the

normalistas, who certainly did not know the breadth of the municipal

government’s power in Iguala, were treated as hitmen. They were

persecuted with the viciousness reserved for rival cartels. In

successive waves, the police attacked the students ruthlessly. Their

desperate attempts to flee by seizing some buses came to nothing. Two

died by gunshot, another was skinned alive. Three innocent bystanders

who were mistaken for students were also shot and killed. During the

chase, dozens of students were arrested and taken to Iguala police

headquarters. No one gave the order to stop. The clock was still

running.

The leader of the hitmen, Gildardo López Astudillo, warned

the highest-ranking leader of Guerreros Unidos, Sidronio Casarrubias

Salgado, that Los Rojos, the rival cartel against which Guerreros Unidos

was fighting a vicious war, were responsible for the rampage. Sidronio

gave the order to “defend the territory.”

In a well-designed extermination campaign, possibly the

product of previous experiments of a similar nature, Cocula officers

picked the students up from police headquarters in Iguala, changed their

license plates, and then handed them over to the cartel’s hitmen at

Loma de Coyote. Everything was organized so as not to leave any trace.

Under the dim moonlight, packed like livestock in a truck

and van, the students were taken to Cocula’s landfill site. It was a

trip to hell. Many students, maybe 15 of them, badly hurt and beaten,

suffocated to death during the ride. Upon arrival at the garbage site,

the survivors were taken out one by one. They were forced to walk a good

while with their hands behind their heads, and then to lie down on the

ground and answer questions. The hitmen wanted to know why they had come

to Iguala and whether they belonged to a rival cartel. According to the

confessions of people arrested in relation to the case, the terrified

normalistas said they were students and that they did not have anything

to do with drugs. That did not help. Once the interrogation was over,

they were shot in the head. The main executioners – though they had help

from other hitmen – were Patricio “El Pato” Reyes Landa, Jonathan “El

Jona” Osorio Gómez and Agustín “El Chereje” García Reyes.

The men prepared a huge pyre at the dump site by putting

down a layer of tires and then another layer of wood on a round bed of

stones. They placed the bodies on top and doused them with gasoline and

diesel.

The bonfire lit up Mexico’s darkest night. The men fed the

flames for hours before feeling free enough to step away, leaving the

fire to burn out. Just after 5pm, after throwing dirt on top, they

approached the remains, examined them carefully and put them in eight

big black garbage bags. They left the dumping site at dusk. On the way

back, they threw the bags into the San Juan River.

It would take Mexico a few days to wake up to the horror of their actions.

No comments:

Post a Comment