By Beverly Bandler

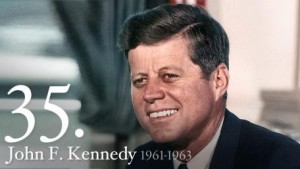

The special quality of John Fitzgerald Kennedy still defies those who would diminish him. He touched something in the American spirit. It lives on 51 years after his death.

And, in an era when many Democrats shy from a political fight and reject the “liberal” label as somehow too controversial, it is worth recalling the more courageous attitude of John F. Kennedy.

“What do our opponents mean when they apply to us the label ‘Liberal’?” Kennedy asked in accepting the New York Liberal Party’s presidential endorsement in 1960. “If by a ‘Liberal’ they mean someone who looks ahead and not behind, someone who welcomes new ideas without rigid reactions, someone who cares about the welfare of the people — their health, their housing, their schools, their jobs, their civil rights, and their civil liberties — someone who believes we can break through the stalemate and suspicions that grip us in our policies abroad, if that is what they mean by a ‘Liberal,’ then I’m proud to say I’m a ‘Liberal.’”

John Fitzgerald Kennedy also said the essential question everyone wants to know about a president is, “What’s he like?” quotes journalist John Dickerson.

JFK has been described as charming, witty, contradictory, elusive, inspiring. The respected American journalist Hugh Sidey (1927-2005) covered the White House and the American presidency for Time Magazine for close to half a century. Said Sidey: ”The special quality of John Kennedy that still defies those who would diminish him is that he touched something in the American spirit and it lives on.”

That mix of personal magnetism and practical idealism made Kennedy the iconic leader who inspired millions although his presidency was cut short after less than three years by an assassin’s bullet.

Journalist, friend and neighbor Ben Bradlee (1921-2014) described Kennedy as “graceful, gay, funny, witty, teasing and teasable, forgiving, hungry, incapable of being corny, restless, interesting, interested, exuberant, blunt, profane, and loving. He was all of those … and more.”

For those of us who came of age in the repressive 1950s, an era of not only McCarthyism but unabashed hypocrisy, double standards and deadening conformity, the urbane and charismatic Jack Kennedy represented a welcome new generation of youth, vigor, and optimism, one dedicated to public service and to country in the best sense of the word “patriotism.”

The aura of youth and vigor JFK conveyed is even more amazing given the extent of his medical issues, which were hidden from the public. According to one of his doctors, Dr. Jeffrey A. Kelman, “The most remarkable thing was the extent to which Kennedy was in pain every day of his presidency.”

John Kennedy suffered from severe health problems all his life. His childhood in the 1920s was a constant saga of childhood maladies — bronchitis, chicken pox, ear infections, German measles, measles, mumps, whooping cough. He came down with scarlet fever when he was three months shy of three years of age. “His illnesses filled the family with anxiety about his survival,” writes historian Robert Dallek.

At 13, Kennedy was afflicted with an undiagnosed and unsolved illness, suffering from dizziness and weakness, fatigue, and abdominal pains. At 15, he weighed only 117 pounds.

By the end of January 1936 at 19, he was more worried than ever about his health, though he continued to use humor to defend himself against thoughts of dying: “Took a peak [sic] at my chart yesterday and could see that they were mentally measuring me for a coffin. Eat drink & make Olive [his current girlfriend], as tomorrow or next week we attend my funeral. I think the Rockefeller Institute may take my case…”

Reading John F. Kennedy’s medical history is reading a profile in constant suffering. Serious back problems added to Kennedy’s health miseries from 1940. “For all the accuracy of the popular accounts praising Kennedy’s valor on PT-109,” writes Dallek, “the larger story of his endurance has not been told.”

Except for his chronic back pain, which he could not hide, neither his commanding officer nor his crew were aware of the challenge of constant illness and pain. Despite his medical difficulties – fatigue, nausea and vomiting – “symptoms of the as yet undiagnosed Addison’s disease,” Kennedy “like a skeleton, thin and drawn” ran successfully for a House seat in 1946.

Kennedy was diagnosed with Addison’s disease, a hormonal deficiency that affects the kidneys, while in London in 1947. The doctor predicted that “he hasn’t got a year to live.” According to Dallek: “On his way home to the United States, on the Queen Mary, Kennedy became so sick that upon arrival a priest was brought aboard to give him last rites before he was carried off the ship on a stretcher.” By 1950 he was suffering almost constant lower-back aches and spasms.

Dallek continues the litany of John F. Kennedy’s medical tribulations: “In 1952, during a successful campaign to replace Henry Cabot Lodge as senator from Massachusetts, Kennedy suffered headaches, upper respiratory infections, stomach aches, urinary-tract discomfort, and nearly unceasing back pain.

“He consulted an ear, nose, and throat specialist about his headaches; took anti-spasmodics and applied heat fifteen minutes a day to ease his stomach troubles; consulted urologists about his bladder and prostate discomfort; had DOCA pellets implanted and took daily oral doses of cortisone to control his Addison’s disease; and struggled unsuccessfully to find relief from his back miseries.

“Dave Powers, one of Kennedy’s principal aides, remembers that at the end of each day on the road during the [1952] campaign, Kennedy would climb into the back seat of the car, where ‘he would lean back … and close his eyes in pain.’ At the hotel he would use crutches to get himself up stairs and then soak in a hot bath for an hour before going to bed. ‘The pain,’ Powers adds, ‘often made him tense and irritable with his fellow travelers.’ ”

“From May of 1955 until October of 1957,” notes the historian, “as he tried to get the 1956 vice-presidential nomination and then began organizing his presidential campaign, Kennedy was hospitalized nine times, for a total of forty-five days, including one nineteen-day stretch and two week-long stays. The record of these two and a half years reads like the ordeal of an old man, not one in his late thirties, in the prime of life.”

Dallek quotes Powers’s whisper to another Kennedy aide, Kenneth O’Donnell in February of 1960 when, during the presidential campaign, Kennedy stood for hours in the freezing cold shaking hands with workers arriving at a meatpacking plant in Wisconsin: “God, if I had his money, I’d be down there on the patio at Palm Beach.”

The full extent of Kennedy’s medical maladies was not known until 2002, the result of Dallek’s being entrusted with the review of a collection of JFK’s papers for the years 1955-1963. The historian writes that after reaching the White House, Kennedy believed it was more essential than ever to hide his afflictions.

That a rumored “legendary love life,” “obsessive womanizing,” the many tales of sexual “hijinks” or “sexual escapades” were attributed to him (consistently kept alive by the amazingly self-righteous, and perhaps envious, members of the “conservative” Noise Machine) makes JFK more remarkable in the 24 hours a day by which he, like the rest of us, was limited.

There have been many “second assassination” attempts by various right-wing hit men and seekers of quick bucks who seduce the gullible with the salacious and sensational (historian Garry Wills dispatches “investigative reporter” Seymour Hersh’s book on “Camelot” in the recommended reading list below).

The sex stories may or may not be true, in part or in whole, but there seem to be far more rumors, gossip and allegations without evidence spun for political purposes than documented history. Wills points out that health, not sex, was the real Kennedy secret.

Dallek makes the assessment that: “There is no evidence that JFK’s physical torments played any significant part in shaping the successes or shortcomings of his public actions, either before or during his presidency. Prescribed medicines and the program of exercises begun in the fall of 1961, combined with his intelligence, knowledge of history, and determination to manage presidential challenges, allowed him to address potentially disastrous problems sensibly.”

The story that the Right does not want Americans to know: “a story of iron-willed fortitude in mastering the difficulties of chronic illness,” Dallek succinctly puts it.

The anti-Kennedy spinning continues more than 50 years since JFK’s assassination in a non-ending effort of the Right to diminish the Kennedy legend. What is important in his painfully aborted presidency: the serious challenges he faced and how he faced them — and indeed, the challenges were serious.

Not open to dispute is John Kennedy’s interest in history and in words. In response to the charge that Barack Obama’s rhetorical skills during his 2008 campaign were “just words,” Ted Sorensen, JFK’s speechwriter, right hand, alter ego and “intellectual blood bank”: told the Boston Globe: ”‘Just words’ is how a president manages to operate … how he engages the spirit of progress for the country.”

To know John Fitzgerald Kennedy is to know his words, and while Sorensen’s wordsmithing brilliance playing a key role in many, if not most of Kennedy’s speeches, as Sorensen himself said, all the words reflected Kennedy’s philosophy and policies.

To count which words originated with Sorensen or which came from Kennedy is not as important as the words used, the ideas conveyed, the messages made effective in his letters, speeches and news conferences. The words he spoke, the words he wrote were John Kennedy’s words.

One of his most memorable speeches, and some consider his “finest moment,” was JFK’s June 11, 1963 televised speech to the nation in which a U.S. president for the first time framed civil rights as a national “moral issue.”

Peniel E. Joseph, founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and Tufts University history professor, believes the June 1963 televised speech “might have been the single most important day in civil rights history.”

The President responded to the attempt by Alabama’s Governor George Wallace to block the integration of the University of Alabama with the enrollment of two black students. Joseph reminds us that:

“It seems obvious today that civil rights should be spoken of in universal terms, but at the time many white Americans still saw it as a regional, largely political question. And yet here was the leader of the country, asking ‘every American, regardless of where he lives,’ to ‘stop and examine his conscience.’ ”

Just after midnight and a few hours after JFK’s speech, Mississippi civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who had fought in World War II from 1943 to 1945 in the European Theater and the Battle of Normandy, was shot in his own driveway in Jackson. NAACP T-shirts that read “Jim Crow Must Go” were in his arms.

Initially refused entry at the local hospital because of his color, he died there 50 minutes later. Arrested for Evers’ murder on June 21, 1963, white supremacist Byron De La Beckwith lived as a free man for much of the three decades following the 1963 killing because of failure to reach a verdict in two trials. In 1994, based on new evidence, De La Beckwith was convicted of Evers’ murder. He died in prison in 2001.

Civil Rights was just one of the major crises that John F. Kennedy faced in the 1,036 days of his presidency. Others included:

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 (4 June – 9 November) is considered the last major politico-military European incident of the Cold War. The three-year crisis evolved from the 1958 Soviet Union ultimatum that the Western powers withdraw from Berlin. Complex negotiations were made more so by the fallout from Gary Powers’s failed U-2 spy flight on May 1, 1960.

Kennedy met with Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna June 4, 1961. The serious confrontation (JFK briefly considered a nuclear first-strike plan in case the crisis turned violent) culminated with the city’s de facto partition with the East German erection of the Berlin Wall.

Shortly after the wall was erected, a standoff between U.S. and Soviet troops on either side of the checkpoint led to one of the tensest moments in the Cold War in Europe. The standoff ended peacefully when Kennedy made use of back channels to suggest that if Khrushchev removed his tanks, the U.S. army would reciprocate.

The 1962 Clash with Big Steel Kennedy was 44 and had been in office 16 months when he had a confrontation with Big Steel. The President invested a great deal of effort in brokering an unwritten, complex deal between the powerful U.S. steel industry and the United Steelworkers of America on March 31 that called for a modest wage increase as the government sought to hold down inflation.

Ten days later, however, Roger M. Blough, leader of U.S. Steel and Big Steel’s principal spokesperson, flew to Washington and handed Kennedy a press release announcing the intention of the U.S. steel industry to unilaterally raise a basket of steel prices by a scale averaging $6 a ton. Kennedy was furious and was said to have felt he was doubled-crossed. He denounced the increase as “unjustifiable and irresponsible.”

In his nationally televised press conference of April 11, 1962, Kennedy described Blough as one of: “a tiny handful of steel executives whose pursuit of private power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility.” Seeing the action by Big Steel as not only inflationary but as an effort to challenge his authority and discredit him, Kennedy responded aggressively with a counter attack. Big Steel rolled back the proposed price hike.

The 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion The Cuban Revolution (1953-1959), led by Fidel Castro, ousted President Fulgencio Batista, a corrupt and brutal anti-communist dictator who had turned Cuba into a police state. Batista had lucrative relationships with the American mafia and large multinational American corporations operating in Cuba, and was supported by the U.S. until 1959.

The U.S. was alarmed by the establishment of the first communist state in the Western Hemisphere. In March 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower approved the top-secret covert action against the Castro regime, known as JMARC, and allocated $13.1 million to the CIA in March 1960 for the plan, which was supported by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Kennedy inherited the plan already well developed, and in April 1961, about 1,400 Cuban exiles trained and funded by the CIA landed near the Bay of Pigs with the intent of overthrowing Castro. The invasion ended in disaster, partially because a first wave of U.S. bombers missed their targets and a second air strike was called off.

Reportedly, Kennedy began to suspect that the plan the CIA had promised that would be “both clandestine and successful” was “too large to be clandestine and too small to be successful.” The conclusion of historians is that JFK was manipulated, deliberately led into a trap — that the CIA and Joint Chiefs knew that the invasion would falter and Kennedy would be forced to send in U.S. military.

The invasion did falter. The President rejected the proposal to send in U.S. military fearing an ignition of World War III. The invasion failed in less than a day — 114 were killed and over 1,100 were taken prisoner. Kennedy took responsibility for the disaster but was bitter at what he considered a deadly deception: “I want to splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter it to the winds.”

While some believe that Kennedy wanted to oust Castro to prove that he and the U.S. were serious about winning the Cold War, others believe the President found himself trapped in a CIA-Joint Chiefs of Staff subterfuge. According to the JFK Library, the Bay of Pigs fiasco was the basis for the initiation of Operation Mongoose — a plan to sabotage and destabilize the Cuban government and economy. It has been argued that the Bay of Pigs gave rise to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and quite possibly, the assassination of John F. Kennedy. []

Operation Northwoods After the 1961 failure of the Bay of Pigs, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (General Lyman Lemnitzer, Chairman) proposed Operation Northwoods to Kennedy in the spring of 1962. Northwoods was a plan to create domestic terrorist events that included shooting down Americans in the streets of Miami and Washington, D.C., stirring up American fear and hatred of Castro sufficient to build support for a war against Cuba. JFK rejected the plan.

The Cuban Missile Crisis The crisis lasted for 13 terrifying days. In October 1962, at the height of Cold War tensions, the United States and the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) came close to nuclear war. Earlier in September, U-2 spy planes discovered that the Soviet Union was building surface-to-air missile (SAM) launch sites and that Soviet ships were arriving in Cuba – it was feared carrying weapons.

The SAMS were considered defensive in Cuba. The US considered the SAMS offensive. Oct. 15 photographs revealed that the Soviet Union was placing long-range missiles in Cuba. Politically, Kennedy was burdened with the Bay of Pigs disaster fallout and faced opposition from a combination of Republicans and conservative southern Democrats in Congress who were trying to make Cuba a midterms campaign issue.

Kennedy met with the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. Strategies considered: Do nothing. Negotiation. Invasion. Blockade. Bomb Missile Bases. Use Nuclear Weapons. The CIA and military favored a preemptive attack on the missile sites and tried to pressure Kennedy. The majority gradually began to favor a naval blockade, which he accepted. The President refused to be pushed into bombing Cuba even when a U-2 plane had been shot down over Cuba.

Remarkable and secret correspondence between Soviet premier Khrushchev and Kennedy in which they grew to trust one another (the letters were smuggled) resulted in a deal: the Soviets would remove their missiles in Cuba. The Americans would remove their nuclear bases in Turkey and would promise not to invade Cuba.

It is to the credit of both Kennedy and Khrushchev that the possibility of a nuclear holocaust that would have multiplied the explosive power of the Hiroshima bomb thousands of times was avoided. The missile crisis is considered probably the most dangerous moment in human history. The peaceful resolution through diplomacy resulted in some constructive developments of the Cold War.

JFK and Vietnam War In its entirety, the Vietnam war lasted from 1946 to 1975. For America, one historian calls it “America’s longest war,” dating it from 1950, with the fateful U.S. pledge of $15 million worth of military aid to France to help them fight in Vietnam, to 1975. The official American phase: 1964 (Gulf of Tonkin Incident) to 1973.

This long and costly armed conflict between the communist regime of North Vietnam and its southern allies, the Viet Cong, against the South Vietnamese government and the latter’s principal ally, the United States, ended with the withdrawal of U.S. forces in 1973 and the unification of Vietnam under communist control two years later. More than 3 million people, including 58,000 Americans, were killed in the conflict. The monetary cost to the U.S. between 1965 and 1975 is estimated at $111 billion, around $800 billion in today’s dollars.

Kennedy inherited the legacies of President Eisenhower, and the mindset of advisors who saw Vietnam as a continuation of World War II with the new enemy our old ally, the Soviet Union. This worldview was oblivious to the anti-colonialism forces born in the late 19th century that would flower in force following 1945.

History reveals that Kennedy was the focus of a power struggle within his own administration advisors, who included the CIA and the military that possessed a kind of “Dr. Strangelove” mentality and who consistently conspired to deceive him and push the U.S. into combat (Kennedy criticized Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles for contemplating the use of atomic weapons at Dien Bien Phu to bail out the French in 1954).

Kennedy visited Saigon in 1951 and met with diplomacy expert Edmund Gullion, the U.S. consul, who told him it would be a disaster to follow the French example in Vietnam. Diplomat Gullion is given credit for altering Kennedy’s view on the Cold War and the muscular way it was being fought in the Third World. Kennedy subtly changed foreign policy to break the “Eisenhower/Dulles Cold War consensus” after he gained office — not only on Vietnam but in Laos, Indonesia and Congo.

According to one historian: “Ironically, while Eisenhower’s supposedly cautious approach in foreign policy had frequently been contrasted with his successors’ apparent aggressiveness, Kennedy spent much of his term resisting policies developed and approved under Eisenhower. In spite of some hawkish speeches to the contrary, perhaps for the purpose of showing that he was willing to escalate American involvement if necessary to placate the politically aggressive hard right, his strategy for Vietnam was really a counter-insurgency strategy in which Americans would act as trainers and supporters of the South Vietnamese. He resisted a full-fledged combat role for the U.S., which in fact, was eventually pursued and that proved disastrous.

That President Kennedy made the decision on Oct. 2, 1963, to begin the withdrawal American forces from Vietnam is thoroughly documented. One historian admitted to his surprise: “What strikes anyone reading the veritable mountain of documents relating to Vietnam, is that the only high official in the Kennedy administration who consistently opposed the commitment of U.S. combat forces was the president.”

Ben Bradlee once quoted Kennedy as saying: “The first advice I’m going to give my successor is to watch the generals and to avoid feeling that just because they were military men their opinions on military matters were worth a damn.”

That attitude was reinforced by the growing casualty lists among the U.S. military advisers sent to Vietnam. On Nov. 21, 1963, a day before his death, Kennedy was quoted as saying, “I’ve just been given a list of the most recent casualties in Vietnam. We’re losing too damned many people over there. It’s time for us to get out. The Vietnamese aren’t fighting for themselves. We’re the ones who are doing the fighting. After I come back from Texas, that’s going to change. There’s no reason for us to lose another man over there. Vietnam is not worth another American life.”

Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty On Aug. 5, 1963, after more than eight years of difficult negotiations, the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union signed the limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. It was the first arms control agreement of the Cold War.

The destruction of two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, by U.S. atomic bombs in August 1945 that killed 70,000 people instantly and another 70,000 in five years, all mostly innocent noncombatants, marked the beginning of the nuclear age. In 1959, radioactive deposits were found in wheat and milk in the northern United States. Scientists and the public gradually became aware of radioactive fallout and began to raise their voices against nuclear testing.

Kennedy had supported a ban on nuclear weapons testing since 1956. He believed a ban would prevent other countries from obtaining nuclear weapons, and took a strong stand on the issue in the 1960 presidential campaign. Kennedy’s strong stand that called for a shift in nuclear policy faced strong opposition.

In August, polling showed 80 percent of the public opposed the treaty. Working with a Citizens Committee, the President succeeded in reversing the public’s attitude in little over a month. Although it would be another quarter of a century before the global Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty would end below-ground nuclear tests, the partial test ban was an historic achievement.

In addition, there was the creation in late 1960 of the innovative Peace Corps of “talented men and women” who would dedicate themselves to the progress and peace of developing countries. The Alliance for Progress initiated in 1961 aimed at establishing economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America. Kennedy appointed his brother Robert Kennedy as Attorney General who would fight “the enemy within” — organized crime. Organized crime convictions increased from 14 in 1960 to 373 in 1963.

Kennedy told the nation on May 25, 1961, that “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.” Eight years later two American astronauts walked on the Moon.

It is perplexing that so many continue to be cavalierly dismissive of Kennedy’s extraordinary accomplishments, and when the latter are seen in the light of his own medical challenges, they become significantly more extraordinary.

Also amazing is how some journalists and historians seem incapable of understanding who Kennedy was and who are determined to re-write history. That he has been characterized as “always hawkish,” a “functional representative” of American elites, and that he was not “the ardent liberal hero” his admirers have made of him since 1963 are attacks contradicted by both his words and his actions.

It is clear that Kennedy was consistently on the side of economic, political and social progress. He was a New Dealer who tried to “restart” FDR’s New Deal, which had been “betrayed” by Truman and “put on ice” by Eisenhower, moving it further along the path of science and technology. He believed that “if we can’t help the poor we can’t save the rich.”

JFK was not a “free marketer” nor a “Keynesian,” but has been described as a “Hamiltonian dirigiste” who supported the nation-state’s role in maximizing economic progress, producing full employment, rising standards of living, and scientific and technological innovation. He was a man of enormous political courage on the side of peace, his own “portrait in courage.”

Kennedy was a threat to powerful forces, especially the military/industrial complex, Big Business, social conservatives, all determined to eliminate government, determined to kill liberalism, progressivism and the New Deal — the “invisible hands” identified by historian Kim Phillips-Fein. “Invisible hands” of right-wing extremism were Kennedy’s and progressivism’s implacable enemies.

“To the Establishment, JFK was a threat. He did represent change — right up until the moment the shots rang out in Dealey Plaza,” wrote author and JFK assassination expert Gary L. Aguilar. Indeed, there is evidence that suggests his murder November 22, 1963, was connected to these reactionary “will to power” pro-war forces. The same reactionary forces continue to be Kennedy’s enemies today, the enemies of progress and peace, of democracy itself.

American journalist and political commentator E.J. Dionne Jr. quoted journalist and historian Theodore H. White:

“The dogmas of his antagonists made clear the quality of the protagonist. For John F. Kennedy, above all, was a man of reason, and the thrust he brought to American and world affairs was the thrust of reason. Not that he had a blueprint of the future, ever, in his mind. Rather his was the reason of the explorer, the man who probes to learn, the man who reaches and must go farther to find out. … He was always learning; his curiosity was total; no one could come out of his presence without coming away combed of every shred of information or impression the President found interesting.”

Kennedy’s own words, spoken in his famous address at American University on June 10, 1963: “I have … chosen this time and this place to discuss a topic on which ignorance too often bounds and the truth is too rarely perceived — yet it is the most important topic on earth: world peace. What kind of peace do I mean? What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave.

“I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children — not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women — not merely peace in our time but peace for all time. …

“I am not referring to the absolute, infinite concept of peace and good will of which some fantasies and fanatics dream. … Let us focus instead on a more practical, more attainable peace – based not on a sudden revolution in human nature but on a gradual evolution in human institutions – on a series of concrete actions and effective agreements which are in the interest of all concerned.

“There is no single, simple key to this peace – no grand or magic formula to be adopted by one or two powers. Genuine peace must be the product of many nations, the sum of many acts. It must be dynamic, not static, changing to meet the challenge of each new generation. For peace is a process – a way of solving problems. …

“Our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal.”

Beverly Bandler’s public affairs career spans some 40 years. Her credentials include serving as president of the state-level League of Women Voters of the Virgin Islands and extensive public education efforts in the Washington, D.C. area for 16 years. She writes from Mexico.

No comments:

Post a Comment